Peptides: The Small Molecules That Changed Science Forever

This article is for educational purposes only. The compounds discussed are classified as research chemicals. They are not approved by the FDA for human consumption and are not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease. References to scientific studies are presented in a research context only. Nothing in this article should be interpreted as medical advice or as encouragement for personal use.

Peptides have become an explosive topic across the fitness world, and are now fully mainstream in 2025.

It is my view that the best way to understand any subject is to know its origins and history.

While I have my personal experiences with peptides, I wrote this article to provide a contextual overview, answer common questions about them, and provide the education for you to make a more informed decision on whether they might be of personal interest to you and your health goals.

Starting from the Beginning: Where “Peptides” Got Their Name

In the early 1900s, the German chemist Emil Fischer was fresh off his 1902 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for explaining the chemistry of sugars and purines.1 Soon after, he turned to a new puzzle: how do amino acids (the small nitrogen-based molecules known as the building blocks of proteins) join together to form larger structures?

Fischer noticed something intriguing during his research. Sometimes amino acids linked into shorter chains that weren’t quite full sized proteins, but also weren’t just free-floating molecules either. They were of an “in-between” size.

He named these types of molecules peptides. The label borrowed inspiration from the Greek word peptos2, meaning “digested” or “softened.” It was a nod to how these chains were seen as partially broken-down proteins.

In science, the language used in description is of critical importance. Words shape how we think. When Fischer gave these little chains a name, he carved out an entirely new category of biology that scientists would spend the next century obsessing over.

Peptides.

Fischer would go on to prove that amino acids join through special chemical links we now call peptide bonds.3 A peptide bond is a type of covalent bond, that links amino acids together into a sequence, forming a chain-like structure.

Stack enough of those links and you get a polypeptide: a longer chain that twists and folds into the complex shapes we call proteins. Those folds are not random, they are what give proteins their powers, from carrying oxygen in your blood to making muscles contract.

Without peptide bonds holding everything in place, the entire system of life would unravel. Peptides can be seen as the glue and substrate of living system. Peptides like insulin regulate blood sugar. Peptide chains knit collagen into the scaffolding that keeps skin firm.

They are the links that hold receptors together, the tiny antennae that let cells talk to each other across the body. Fischer’s work revealed that these short chains were not trivial fragments. They could carry signals every bit as powerful as entire proteins.

Peptides changed the way scientists thought about biology. Suddenly, life could be studied not only in the grand architecture of DNA and proteins, but also in the nimble, fast-moving world of peptides, which are essentially the messengers in between.

What Peptides Actually Are

We've said that peptides are smaller pieces of larger proteins, but lets break that down further. What does “peptide” really mean in plain English? Visualization is the best way to understand this

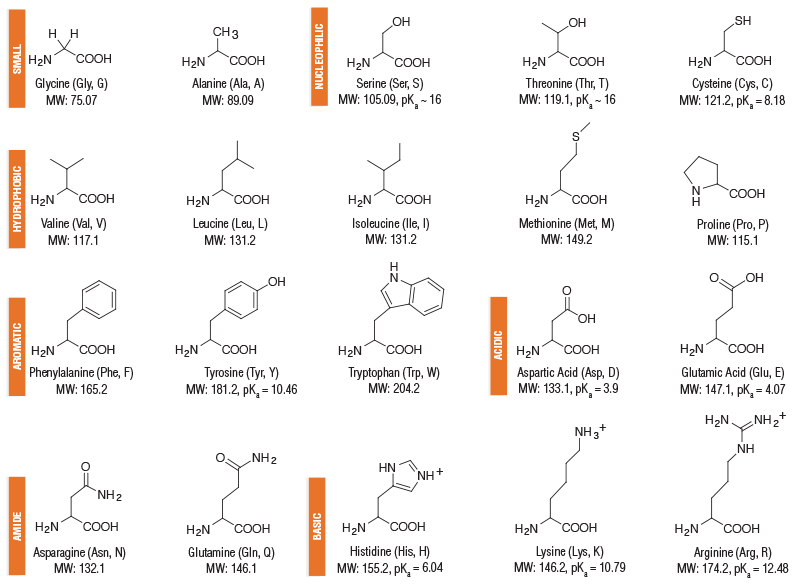

There are 20 Amino acids which constitute an alphabet for the body to build with. These aminos are comprised of the fundamental molecules of biological life; carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, nitrogen, and sulfur (for cysteine)

Peptides are like words formed from Amino Acids. Link a few letters together, and suddenly you get meaning: a short message the body can understand.

Proteins are the essays or novels. Long chains built from many peptide “words,” telling complex stories and running the machinery of life.

There are further classifications of amino acids, and proteins, which gets very detailed very fast. A long lesson in organic chemistry goes beyond the scope of this article. We will stick to Peptides for now.

The basics to know is that peptides are intermediaries between amino acids and proteins. They are the switchboard operators of biology, turning signals into action. Without them, your body’s messages would get lost. With them, the whole system stays in sync.

There are THOUSANDS of peptides in the body. Peptides are arguably “natural” from a medicinal standpoint. The peptides that are used today in medicine and biohacking have their origins in the body's own naturally occurring peptides.

Different Types of Peptides

Not all peptides look or act the same. To use the language metaphor, just as words can be nouns, verbs, adverbs, and adjectives, so too do peptides come in many forms. Science has a few ways of classifying them.

By Length

Dipeptides: just two amino acids linked. Example: carnosine, found in muscle.

Tripeptides: three amino acids. Example: glutathione, a key antioxidant.

Oligopeptides: a handful (2–20 amino acids).

Polypeptides: longer chains (20–50). Anything beyond ~50 is usually called a protein.

Think of it like texting: short chains are quick one-liners, long ones become sentences and paragraphs.

By Source

Ribosomal peptides: built by your own cells. These include hormones like insulin, oxytocin, and glucagon.

Non-ribosomal peptides: crafted by bacteria and fungi using specialized enzymes. Famous examples are antibiotics like vancomycin and daptomycin.

By Function

Hormonal peptides: regulate processes in the body (insulin, GLP-1)

Neuroactive peptides: act as messengers in the brain (endorphins for pleasure, substance P for pain).

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs): your body’s built-in antibiotics (defensins, magainins).

Signal peptides: like postal codes, tagging proteins so they reach the right place in the cell.

Cosmetic peptides: These are studied in skin research (like palmitoyl pentapeptides for collagen, or tripeptide glycyl-L-histidyl-L-lysine, popularly known as GHKcu).

By Structure

Linear peptides: straight chains, flexible but fragile.

Cyclic peptides: looped into rings, tougher and more stable.

Modified peptides: chemically tweaked for durability, for example, semaglutide with its fatty acid “tail” that keeps it circulating longer in the body.

Shape matters. A loop can survive longer, while a modified chain can be engineered to last hours or even days instead of minutes.

The Turning Point: When Peptides Enter Medicine

Insulin: The First Blockbuster Peptide 6

In 1921, two young researchers, Frederick Banting and Charles Best, performed what can only be described as a medical miracle. Working in a modest Toronto lab, they isolated insulin, a peptide hormone the body naturally produces to regulate blood sugar.

To understand the magnitude: before insulin, a diagnosis of Type 1 diabetes was essentially a death sentence. Patients, often children, were put on starvation diets to stretch out their lives by weeks or months.

There was no real treatment, only a slow decline. It was the first time a peptide had stepped into the spotlight as a life-saving therapy. It was the dawn of modern peptide therapeutics and set the stage for everything that came after.

Oxytocin and Vasopressin (1950s) 7

By the 1950s, peptide science took another leap forward. Vincent du Vigneaud pulled off what sounded like science fiction at the time: he built a hormone, oxytocin, entirely from scratch in the lab. For that, he was awarded the 1955 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

Why did it matter so much? Oxytocin was not a random peptide. It’s the hormone that helps trigger childbirth, strengthens emotional bonds, and even plays a role in trust and social connection. Until then, hormones were things we could only extract from living tissue.

For the first time, scientists saw that the tiny messages running the body could be recreated and, one day, redesigned. It opened the door to a future where peptides were not only discovered but deliberately engineered to solve human problems.

Antibiotics: Nature’s Chemical Warfare 8

Meanwhile, nature had already been making peptides long before humans caught on. Microbes such as bacteria and fungi used them as weapons in microscopic turf wars. Instead of straight chains, many of these were tougher, looped molecules built to survive harsh conditions.

From that hidden battlefield came two breakthroughs: bacitracin and vancomycin. These non-ribosomal peptides became some of our most powerful antibiotics, turning the tide against infections that once killed millions.

We did not invent antibiotics out of a vacuum. We uncovered nature’s arsenal and learned how to use it. What microbes created to fight each other, we borrowed to save ourselves.

Today in 2025: 80+ Peptide Drugs and Counting 9

Fast forward to today and the field has exploded. There are now more than 80 peptide drugs approved worldwide. They are part of treatments for HIV, cancer, and various metabolic diseases.

While peptides are novel to the general public, you now know they have existed and been used for decades. Ozempic was their entry into mainstream awareness.

For a medical standpoint, Peptides occupy something of a Goldilocks zone. They are not as bulky and expensive as big biologic drugs and are not as blunt and unpredictable as small molecules. They are precise enough to hit the right target, yet agile enough to actually work in the real world. But economically, peptides are difficult to patent, due to their being easily replicated and modified, and difficult to make profitable, due to the long time periods required to go from Stage 1 to Stage 3 trials to FDA approval. As of today, most peptides exist within the zone of “research chemicals”, and their usage is pioneered through biohacker experimentation.

Peptides likely would have stayed within the grey zone of biohacking and fringe communities indefinitely, had it not been for a major breakthrough drug that we all know today…

GLP-1: The Peptide that entered the Zeitgeist

If insulin was the first peptide to be a blockbuster in mainstream medicine, GLP-1 is the modern sequel that became known in mainstream culture.

GLP-1 (glucagon-like peptide-1) is a 30-amino-acid hormone released in your gut right after you eat.10 It sends three distinct signals at once:

To the pancreas: “Release insulin, but only if blood sugar is high.”

To the stomach: “Slow down. Don’t dump food into the system too fast.”

To the brain: “You’re full. Put down the fork.”

Without GLP-1, blood sugar spikes would be harder to control, and your brain wouldn’t get those satiety cues as clearly. The regulating effects of GLP-1 became of interest to researchers, and various scientists began studying it. The story of what would become Ozempic goes back almost 40 years.

The Origin Story (the abbreviated version)

In the 1930s, a class of gut hormones labeled Incretins had been discovered by Belgian scientist Jean La Barre , who had identified that gut hormones might stimulate the pancreas to release insulin, and decrease blood glucose levels. This discovery was interesting, and he surmised it could be used in diabetes treatment somehow, but it would not be until the 1980s that science built on it further. During this time there were multiple researchers that began to innovate on the incretins and their role in appetite and metabolism. As more specific hormones were identified, the Incretin label was less used, but all of the GLP-1 drugs on market today can be considered incretin hormones.

The discovery and development of what would become GLP-1s wasn’t the work of one lab but a global relay. Each scientist had focused on a different piece of the puzzle.

Svetlana Mojsov, a protein chemist at Rockefeller, went into the lab and started slicing and testing fragments to see which ones actually worked.11

Daniel Drucker at the University of Toronto pushed the question further, chasing how these gut peptides controlled metabolism in living systems.12

Jens Juul Holst, in Copenhagen, tracked the physiology, charting how GLP-1 signals behaved inside the body itself.13

Joel Habener at Harvard mapped the genetic blueprint, showing how the instructions for these hormones were written into our DNA.14

Together, their work integrated into a bigger picture understanding of the gut’s role in biology. The intestine was not only digesting food, it was also acting like an endocrine organ, sending out chemical signals that connected the gut, the brain, and the pancreas.

Svetlana Mojsov made the first breakthrough. She isolated the active GLP-1 fragment and showed in rat pancreas models that it could trigger insulin release. That experiment took incretins from being a biochemical curiosity to a subject of innovation with the potential for pharmaceutical development.15

Daniel Drucker and Jens Juul Holst pushed the story further. They revealed that GLP-1 wasn’t acting in isolation. It was part of a wider gut–brain–pancreas axis, a signaling network that governed appetite, blood sugar, and digestion. 16

Meanwhile, Joel Habener’s lab mapped the genetic blueprint, providing the molecular framework that tied all the pieces together. The result was radical. The gut was not simply a digestive machine. It was behaving like a hormone-secreting organ, broadcasting peptide signals that dictated how the body handled nutrients.

In 2024, Habener, Drucker, Mojsov, and Holst all received the Lasker Award, one of biomedical research’s highest honors. Their work went beyond identifying the hormone, as their discoveries basically rewrote the playbook for metabolic science and paved the way for GLP-1–based therapies that are now changing millions of lives.17

From Incretin to Ozempic.

How did GLP1 go from a hormone though and become a pharmacy drug. This story is simple to understand, although it took decades to develop.

In its natural stage in the body, GLP-1 is fragile. Once released, it is shredded by enzymes and gone in less than 2 minutes. That made it fascinating for researchers but useless as a therapy. They realized it lowered blood sugar, but it was broken down too fast to be useful. You can’t dose a patient with something that disappears almost instantly.

The solution came through bioengineering. Scientists began designing GLP-1 receptor agonists; analogs that mimic GLP-1 but resist being broken down. Some had chemical tweaks. Others were fused to fatty acid “tails” that let them hitch a ride on albumin in the bloodstream, staying active for hours instead of minutes.

That innovation gave rise to an entire drug class:

Exenatide (2005): The first GLP-1 drug, inspired by a peptide in the saliva of the Gila monster. It proved the concept that a fragile gut hormone could be turned into a working therapy.18

Liraglutide (2010): A next-generation version with a fatty acid “tail” that helped it stay in the bloodstream longer. That tweak meant fewer doses and better durability.19

Semaglutide (2017): The breakthrough that pushed GLP-1 into the mainstream. It was more stable, more effective, and the first peptide drug to dominate headlines worldwide 20

Tirzepatide (2022): A new kind of hybrid. It acted on both GLP-1 and another gut hormone, GIP, opening a fresh frontier in how scientists think about metabolic control.21

Retatrutide (coming end of 2026): A triple agonist molecule that acts on GLP-1, GIP, and Glucagon. In Stage 2 trials it outperformed Tirzepatide in weight loss, and has taken off massively in the biohacker obesity research world.

On social media there is often intense fear mongering around GLP1s. But in reality, they have been used for 20 years now, been in development for 4 decades, and their efficacy and safety is well established.

They are also the “poster drugs” for peptide science. Whether you think GLP1s are awful or amazing, they have made peptides mainstream and opened up new frontiers in medicine.

Beyond GLP-1: Peptides in the Biohacker World

Here’s where science and online subcultures collide. Ask a doctor about peptides, and they're likely to respond with caution and skepticism.

Get online though, and look at biohacking forums, subreddits, and youtube, and peptides are discussed with a mix of enthusiasm and openness on their usage. These conversations rarely reflect the cautious language of academic research. Instead you’ll read and watch individuals sharing protocols, sharing stories, and learn about novel effects that mainstream medicine rarely acknowledges.

This is the biohacker world, where millions of people do their own experiments.

And to be VERY clear, practically all peptides are classified as research chemicals, not approved for human use by the FDA or other regulators.

But this is not an obstacle to adventurous people who elect to do their own personal research.

Some peptides that are commonly discussed and have become popular in Biohacking, Fitness, and Athletic Performance world

There are dozens upon dozens of peptides, and this is by no means an exhaustive list. These three are often talked about.

BPC-157: The Healing Peptide

BPC-157 is a synthetic fragment of a protein found in gastric juice. In animal studies, researchers have explored it in the context of tissue repair and gut health. Online communities sometimes refer to it as a “healing peptide,” though this reflects speculation rather than clinical evidence. To date, there are no published human clinical trials demonstrating safety or efficacy, and regulatory bodies classify BPC-157 strictly as a research chemical.22

TB-500: The Regeneration peptide

TB-500 is a synthetic fragment of thymosin beta-4, a naturally occurring protein involved in cell migration. Preclinical studies in animals have examined its potential role in wound-healing processes. In online discussions, it is sometimes portrayed as a tool for “regeneration,” but again, these are cultural narratives rather than scientific consensus. Like BPC-157, TB-500 has no FDA approval and remains untested in human clinical trials. 23

GHKcu: The Beauty Peptide

GHK-Cu is a naturally occurring copper peptide known primarily for its roles in skin regeneration, wound healing, and anti-aging effects, as well as its ability to modulate gene expression for cellular repair and protection. Researched since the 1970s, its become used in an increasing number of high end skincare products, as well biohacking protocols around healing for injuries, muscles, and chronic pain. 24

You are in 100% DIY territory if you elect to Biohack

While animal studies and laboratory research continue, no peptides (except approved prescription drugs under physician guidance) can legally be considered safe or effective for human consumption. They remain research-only substances.

In Summary

Peptides are not empty hype. What was originally a quiet and overlooked field of research that gave us insulin and antibiotics is now a zeitgeist topic thanks to GLP-1 receptor agonists dominating headlines.

Its my personal view that they will eventually redefine pain and injury treatment, metabolic disease treatment, and be a full revolution in medicine by mid century. For now they fuel debates in biohacking forums and fitness circles, and it will be up to scientific research to validate the claims and test the theories.

Scientifically minded individuals are invited to join the Biohacking telegram, where we discuss these topics in detail with other scientific enthusiasts.

If you are interested in Scientific Research with Peptides, my recommended vendor is Elite Research USA. 10AJAC is an affiliate code that will give you 10% off. Peptides are research chemicals first and foremost, and not for human consumption

References

Emil fischer – biographical. (n.d.). NobelPrize.Org. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1902/fischer/biographical/

Peptides. (2011). In Encyclopedia of Cancer (pp. 2813–2814). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-16483-5_6664

Peptide bond—An overview | sciencedirect topics. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/biochemistry-genetics-and-molecular-biology/peptide-bond

Lopez, M. J., & Mohiuddin, S. S. (2025). Biochemistry, essential amino acids. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK557845/4

Pintea, A., Manea, A., Pintea, C., Vlad, R.-A., Bîrsan, M., Antonoaea, P., Rédai, E. M., & Ciurba, A. (2025). Peptides: Emerging Candidates for the Prevention and Treatment of Skin Senescence: A Review. Biomolecules, 15(1), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15010088

Excellence, Um. D. C. of. (2018, July 26). Frederick banting & charles best isolated human insulin on july 27, 1921. UMass Chan Medical School. https://www.umassmed.edu/dcoe/diabetes-education/patient-resources/banting-and-best-discover-insulin/

Vincent du Vigneaud | Nobel Prize, peptide hormones, sulfur chemistry | Britannica. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Vincent-du-Vigneaud

Hutchings, M. I., Truman, A. W., & Wilkinson, B. (2019). Antibiotics: Past, present and future. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 51, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2019.10.008

Otvos, L., & Wade, J. D. (2023). Big peptide drugs in a small molecule world. Frontiers in Chemistry, 11, 1302169. https://doi.org/10.3389/fchem.2023.1302169

ELS, L. C. (2024, February 5). GLP-1 diabetes and weight-loss drug side effects: Harvard Health. https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/glp-1-diabetes-and-weight-loss-drug-side-effects-ozempic-face-and-more

Svetlana mojsov. (n.d.). Greengard Prize. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://www.rockefeller.edu/greengard-prize/recipients/svetlana-mojsov/

Drucker lab broadens focus on gut hormone GLP-1, the ‘Swiss Army knife’ of metabolism. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://deptmedicine.utoronto.ca/news/drucker-lab-broadens-focus-gut-hormone-glp-1-swiss-army-knife-metabolism

Unlocking longevity: Dr. Jens juul holst on glp-1’s life-changing impact on metabolic health. (n.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://blog.insidetracker.com/longevity-by-design-podcast-jens-juul-holst

Habener Receives Gairdner Award. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://hms.harvard.edu/news/habener-receives-gairdner-awa

Friedman, J. M. (n.d.). The discovery and development of GLP-1 based drugs that have revolutionized the treatment of obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 121(39), e2415550121.

(N.d.). Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://hms.harvard.edu/news/gut-hormone-insights

Admin, L. (n.d.). GLP-1-based therapy for obesity. Lasker Foundation. Retrieved September 1, 2025, from https://laskerfoundation.org/winners/glp-1-based-therapy-for-obesity

Triplitt, C., & Chiquette, E. (2006). Exenatide: From the Gila monster to the pharmacy. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association: JAPhA, 46(1), 44–52; quiz 53–55. https://doi.org/10.1331/154434506775268698

Knudsen, L. B., & Lau, J. (2019). The discovery and development of liraglutide and semaglutide. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10, 155. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00155

Guja, C., & Dănciulescu Miulescu, R. (2017). Semaglutide—The “new kid on the block” in the field of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists? Annals of Translational Medicine, 5(23), 475. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.10.09

Tall Bull, S., Nuffer, W., & Trujillo, J. M. (2022). Tirzepatide: A novel, first-in-class, dual GIP/GLP-1 receptor agonist. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications, 36(12), 108332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2022.108332

Józwiak, M., Bauer, M., Kamysz, W., & Kleczkowska, P. (2025). Multifunctionality and Possible Medical Application of the BPC 157 Peptide—Literature and Patent Review. Pharmaceuticals, 18(2), 185. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18020185

Philp, D., & Kleinman, H. K. (2010). Animal studies with thymosin beta, a multifunctional tissue repair and regeneration peptide. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1194, 81–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05479.x

Dou Y, Lee A, Zhu L, Morton J, Ladiges W. The potential of GHK as an anti-aging peptide. Aging Pathobiol Ther. 2020 Mar 27;2(1):58-61. doi: 10.31491/apt.2020.03.014. PMID: 35083444; PMCID: PMC8789089.