Mountain Dog Chest Training

Huge pecs, pain free

Developed pectoral muscles are arguably the singularly most masculine muscle group on the entire male physique.

By way of biology, men naturally have more upper body muscle than women, and in particular men have much larger pectoral muscles. The strongest women struggle to chest press weights that even an average man can lift with ease.

Having a big chest may not be “functional” in the way that shoulders or back or legs are, but it is undeniably imposing and a standout masculine physique feature.

John Meadows had a longevity based approach to chest training. He had reasonably good pectoral genetics, but also paid attention to patterns of strain and injury.

By his own estimate, 25% of the time he started a workout with barbell bench pressing and went up to anything remotely heavy, he would get at least a minor pec strain.

He noticed the same thing with other lifters. There was a widespread belief to always do your hardest and heaviest exercise first, but this create a setup for injury. John trained in the world of hardcore lifters, bodybuilders and powerlifters who competed at a high level.

He witnessed enough strains and tears to realize there had to be a better way.

John was solving three problems simultaneously. Building the chest. Protecting the shoulders. And creating a system that worked for guys in their 30s, 40s, and 50s who could not afford to get injured.

Between my own experience and John’s methodology, this article covers everything you need. The anatomy, the angles, the exercise selection, the sequencing, the programming, and the specific techniques that build slabs of muscle without destroying your joints.

What you’ll learn today (A LOT):

- Why most guys have overdeveloped lower chests, flat upper chests, and chronic shoulder pain, and the exercise sequencing that fixes all three

- The three distinct regions of the chest and why training only one of them with flat pressing creates the imbalance that stalls your development

- Progressive resistance applied to chest, why 60lb dumbbell incline presses done with precision will build more muscle than 100lb sloppy reps

- John’s signature chest exercises that changed how serious lifters approach the muscle

- A complete four-phase chest workout with built-in periodization

Before We Begin

-Eliteresearch is my favorite company for peptide research and unique compounds (like Nostridamus). Use code AJAC10 at checkout

-Preorder Creatine for the Woman in your life from Ferta Supplements

-For the men that want to get their health DIALED IN with the best doctors in the world, work with Velocity

Part 1: Functional Anatomy

Learning anatomy is always easier in person, and trying to describe muscles in words without visuals is difficult. There is no replacement for in person learning. That said, there are THREE muscles you need to understand if you want to build a complete chest. Not two. Three.

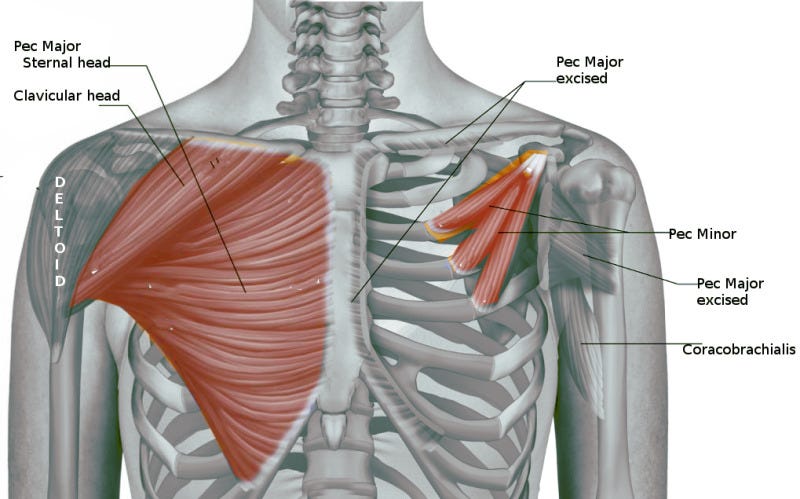

The Pectoralis Major is the big chest muscle that everyone can see. It is the visible portion of the pec on anyone with a functioning body. The pec major is a fan-shaped muscle that attaches to the sternum, the clavicle, the first six or seven costal cartilages, and the aponeurosis of the external oblique. All of those fibers converge laterally and insert onto the humerus.

Here is the part that matters for training. The pec major is divided into three distinct parts based on where the fibers originate, and each part generates tension on a preferred angle (while also overlapping with each other).

The Clavicular Head (Upper Chest). Originates from the anterior surface of the medial half of the clavicle. Its fibers run downward and laterally toward the upper arm. This is the most neglected region in most lifters. It is innervated by the lateral pectoral nerve, a completely separate nerve supply from the rest of the pec.

This is not a trivial detail. It means the clavicular head is essentially a functionally independent muscle that can be preferentially recruited through specific angles and movements. When someone tells you that you “can’t isolate the upper chest,” they are anatomically wrong. Different nerve, different fiber direction, different function. The clavicular head flexes the arm and performs horizontal adduction. Incline pressing between 15 and 45 degrees targets this head directly. A well-developed upper chest creates the shelf that makes the entire pec look full and powerful from the front and the side.

The Sternocostal Head (Middle and Lower Chest). This is the largest part of the pec major. It originates from the anterior surface of the sternum and the upper six costal cartilages. It is innervated by the medial pectoral nerve, again, a different nerve than the clavicular head. The sternocostal head is itself further subdivided into multiple segments. Anatomical research has identified between 2 and 7 distinct segments within the sternocostal head alone.

This is why experienced bodybuilders can develop visible separation between the upper, middle, and lower portions of the sternal chest, the fiber orientations are genuinely different.

The upper sternal fibers run more horizontally, responding to flat pressing.

The lower sternal fibers angle downward, responding to decline pressing and dips.

This head handles adduction and extension of the arm. It is what makes the chest look thick from the side and creates the lower pec shelf.

The Abdominal Head. A variable third head that originates from the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Not everyone has a well-developed abdominal head, and it may be absent entirely in some individuals. When present, it contributes to the lowest fibers of the pec and ties the chest into the upper abdominal region. It is recruited during dips and steep decline movements.

Because the pec major consists of these distinct parts with different origins, different fiber directions, and in the case of the clavicular versus sternocostal heads, entirely different nerve supplies, it is entirely possible to emphasize training EACH section. Do not listen to anyone that says you cannot emphasize training lower, middle, or upper chest. You absolutely can. Depending on the angle of the exercise, a different portion of pectoral fiber will be emphasized.

The Pectoralis Minor is a much smaller muscle that sits underneath the pec major. It attaches to the coracoid process of the scapula and the 3rd, 4th, and 5th ribs. Its primary function is not pressing, it is scapular stabilization. The pec minor protracts and depresses the scapula, pulling the shoulder blade forward and down against the ribcage.

Here is why this matters for chest training. If your pec minor is tight and dysfunctional from years of hunching over a desk, excessive flat pressing, and never stretching, it will pull your shoulders into internal rotation and compromise your shoulder mechanics. This limits your range of motion on every pressing movement and eventually leads to impingement. A dysfunctional pec minor is one of the most common hidden causes of shoulder pain on chest day. John Meadows included a specific exercise for the pec minor, the straight-arm pec minor dip, because he understood that training this muscle directly contributed to both scapular health and overall pec mass.

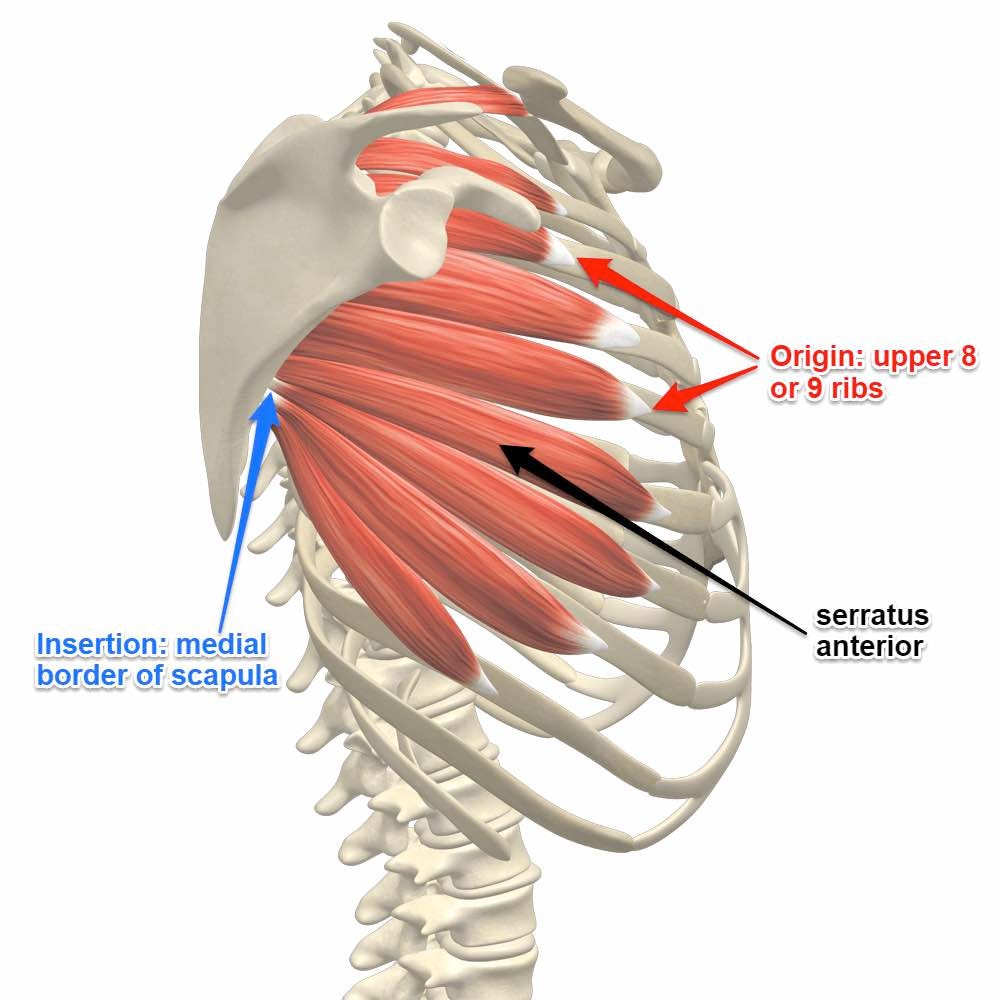

The Serratus Anterior is the third muscle you need to know about, and it is the one almost every lifter ignores. The serratus anterior is a fan-shaped muscle that originates on the lateral surfaces of the first eight or nine ribs and inserts along the medial border of the scapula, wrapping around the ribcage underneath the shoulder blade. It is sometimes called the “boxer’s muscle” because it is responsible for scapular protraction, the forward punching motion of the shoulder blade.

Why does this matter for chest training? Because the serratus anterior is the prime mover in scapular protraction and upward rotation. Every time you press a weight and your shoulder blades move forward around the ribcage, the serratus anterior is doing that work. It stabilizes the scapula against the ribcage during every pressing movement you do. When the serratus is weak or dysfunctional, the scapula wings off the ribcage, your shoulder blade does not track properly, and your pressing strength suffers. You also get compensatory recruitment from the upper traps and levator scapulae, which is why some guys shrug their shoulders up during bench pressing without realizing it.

Dumbbell pullovers, push-up variations with protraction at the top, and overhead pressing all develop the serratus. If you do nothing else, add a set of push-ups with a deliberate “push plus” at the top, pressing your shoulder blades apart at the top of each rep, and your serratus will wake up.

Together, the pec major, pec minor, and serratus anterior perform flexion, adduction, and internal rotation of the humerus, combined with scapular protraction, stabilization, and upward rotation. Practically, this means the chest complex has the function of “pulling” the arm across and towards the center line of the body while simultaneously anchoring the shoulder blade to the ribcage. This flexion, adduction, and internal rotation combine into being able to “push.” The pressing movement is a combination of all three functions, executed across all three muscles.

Part 2: Chest Pressing Technique

This is the best video you will EVER watch on technique for pec training

Your chest muscle can push from THREE distinct directions.

Downward towards the floor. This is dips, lower chest flys, and decline pressing of any kind. Pressing downward always recruits the middle and lower pectorals. This is why DIPS were largely considered the premiere chest exercise before bench press took over. While dips do not emphasize upper chest, they massively work the lower and middle chest. Getting very strong on dips and downward angle pressing will always ensure some level of pectoral development.

Horizontal directly in front of the body. This is pushups, any kind of flat chest press, and middle chest flys. Flat pressing also recruits the anterior deltoid, and depending on your shoulder structure, chest structure, and arm length, flat pressing can be all pecs or a lot of deltoid. Certain exercises like bench press may not be as effective as you want them to be. As every body is unique, it is mandatory to experiment and find what exercises best work the pecs for you on this angle. Slight inclines and slight declines are often superior to the flat bench in recruiting the pecs.

At an angle above the chest to about chin level. This is incline pressing and incline flys. This angle works LESS of the lower chest but emphasizes the upper pec fibers. This is why incline work is essential if you want upper chest development. Incline work will also recruit the anterior deltoid. The classic 45-degree incline bench press works upper chest and deltoids together.

If you want COMPLETE chest development, you must work the chest on ALL three of these angles, not just one.

This is the first mistake guys make. They only train ONE angle, usually flat bench, and neglect the other two. The result John Meadows saw constantly: lower chest is overdeveloped from excessive flat pressing, upper chest is flat and underdeveloped, and shoulder pain is common. That is the default outcome of a “bench press first” chest program.

Part 3: Customize Your Exercises to Suit Your Structure

What does structure mean? Three things.

How deep is your chest wall? The anatomical term for what old school bodybuilders called “chest wall depth” is the anteroposterior thoracic diameter, the front-to-back measurement of the thorax from the sternum to the spine.

This is distinct from the transverse thoracic diameter, which is the side-to-side width of the ribcage. Both measurements together define the overall size and shape of your rib box, the complete bony structure of ribs, sternum, costal cartilages, and thoracic spine that houses the lungs and heart and serves as the skeletal platform on which all your chest muscle sits.

Men with BIG chest naturally have deep and wide ribcages, like Jay Cutler for example. Combined his bone structure with incredible genetics, and you’ve got an elite physique.

Back in the Silver and Golden age of bodybuilding, there were many articles written on how to increase your rib box and why this was essential to having a big chest. Steve Reeves, Reg Park, and Arnold all devoted significant training time to breathing squats and dumbbell pullovers specifically to expand the rib box.

Reg park in his prime

The theory was that you could stretch the costal cartilages, the strips of dense connective tissue that attach the ribs to the sternum, and over time expand the thoracic cage itself.

Whether this actually works in adults is debatable. Modern evidence suggests that real skeletal expansion of the rib box can only occur during the teenage years while the growth plates are still open. After the early twenties, the bones can thicken slightly but they cannot lengthen.

What IS trainable at any age is the musculature surrounding the rib box, the intercostals, serratus anterior, and the pec muscles themselves, along with thoracic mobility and postural positioning that makes the ribcage appear larger and more prominent.

Arm length. Arm length makes a HUGE difference. If you have short arms and a deep chest wall, you will find it far easier to do ANY kind of pressing exercise. The weight is traveling less distance, and your body is naturally structured for better leverage. You will never find a big bencher that has a shallow and narrow chest.

In contrast, if you have very long arms and an average sized rib cage with shallow chest depth, you will likely find it difficult to bench press and it won’t even feel like a chest exercise. To touch the bar to the chest, you have to hyperextend the upper arm past the shoulder joint, which puts all of the stress on the anterior delt. Bench pressing will never be a good chest builder if this is your physique.

Add those factors together. What exercises should you do?

You can divide guys into three general categories.

Big chest structure. The classic exercises will be all you need. Flat bench, incline bench, DB press, incline DB press, dips. Getting progressively stronger on the classic exercises will be your strategy. The only adjustments are grip width for your arm length and being patient enough to follow a program.

Average chest structure. This is the mixed approach. You MUST find your KEY exercises that you can get progressively stronger at. There is no shame in realizing that a low incline Smith machine chest press works better than bench press, or that a hammer incline press works better than incline bench. This middle ground is about tweaking exercises that feel optimal to you. Once you find those movements, you hammer them for the rest of your training life.

Below average structure. If you have a small chest wall, long arms, and most exercises don’t do shit for you, you need to emphasize MUSCLE TENSION, and employ moderate to higher reps. Assess all chest exercises by whether you can FEEL them in the pecs and you get shortening and lengthening of the pectoral muscles. This will probably mean a lot of cable fly presses, hybrid press/flyes, and machines. Bench press isnt going to be your thing. Stop caring about it. DBs you’ll need to be very controlled with arm path and depth and keep the chest wall expanded.

Why higher reps? Because the less fast twitch muscle fiber you have, the less responsive you are to low rep training. If you are NOT fast twitch dominant, doing low reps exclusively won’t yield much muscle growth. Increase your working rep ranges. Working sets in 10-20 rep range.

Part 4: Common Mistakes That Kill Your Chest Development

Half the battle of progress is avoiding doing dumb shit in the gym that does not lead to results. These mistakes apply to almost every man reading this.

Training for low reps and constantly trying to add weight. This is the classic high school bro mistake. You start training, get some newbie strength gains, and then try to max out every week. Strength never goes up. STOP DOING THIS SHIT. Chest strength is built OVER TIME. Testing your strength is not building your strength. Wanting to see what your 1 rep max is every week is pure stupidity. Proper strength training is months of doing rep work and gradually building up in weight. I guarantee you will never make progress if you insist on maxing out all the time.

Too much momentum and crash landing the weight. If you want to feel the pecs work, slow the reps, control the weight with the pecs, and do the lift with controlled technique. If you want to fuck up your shoulders and make no gains, try to do reps with as much momentum as possible while nodding your head up and down with no real control over the weights. This is especially prevalent with bench press, but guys do it with practically every chest exercise. John called this “bounce pressing” and he was right, there is no pec engagement when you are using momentum to move the bar.

Too much barbell pressing. If this approach worked for you by now, you would already know it and wouldn’t be reading this. Heavy bench press is great if it works for you, but for many it is a mediocre-to-poor pec builder. Unless you are a competitive powerlifter or professional athlete that is going to get tested on this lift, there is no reason you NEED to be using it.

Too small a range of motion. Everyone knows what this looks like. It is the guy in the gym who, as the weights get heavier, the range of motion gets cut shorter and shorter. Half range bench press, half range chest presses, half range pec flys. Your strength will “plateau” because you are training like a dumbass, and you will be deluded into thinking you are stronger than you are.

Training chest too often. It is a common bro habit to train upper body over lower body, and to train chest shoulders arms over everything else. Training chest high frequency CAN work for very short periods of time, but those adaptations are largely neurological, not muscular. The shoulder joint and pec tendon and elbow joint can only tolerate so much heavy pressing within a given week. MORE is not automatically better. At most, you can train pecs twice a week. Experiment between a heavy day and a light day, or two medium intensity days. Any more than that, you are setting yourself up for injury and tendonitis.

Trying to train through joint pain. If you have torn up rotator cuffs, your shoulders click and pop when doing anything heavy, you have shoulder impingement, you keep getting pain during certain movements, but you are trying to ignore it and train chest anyway…you are very dumb. Effective training SHOULD NOT HURT. Whether you need physical therapy, better mobility, soft tissue therapy, better exercise selection, better technique, or all of the above, there is no situation where chronic pain is acceptable during a workout.

Part 5: The Meadows Exercise Sequencing System

This is the most important section of this article. Exercise sequencing is what separates John’s chest methodology from everything else.

First: Activate the chest and prepare the shoulders. Before touching any serious weight, you must prepare the shoulder joint and establish a mind-muscle connection with the pecs. Band pull-aparts to activate the rear delts. Light cable flyes to wake up the chest. Internal and external rotation work for shoulder health.

John developed a specific chest activation sequence: 20 band pull-aparts, 15 light cable flyes, 10 push-up holds at the bottom position, then 5 slow controlled push-ups. This took five minutes and eliminated the majority of shoulder issues his clients experienced on chest day. This is not optional.

Second: A dumbbell press or machine press to pump blood into the chest. This is where John broke from conventional wisdom in the most important way. He did NOT start with barbell bench press. Ever.

After years of pec strains from starting with barbell bench or barbell incline, John discovered that beginning with a movement that allowed a full stretch and squeeze, like a dumbbell twist press or machine press, filled the pecs with blood and dramatically reduced injury risk.

The logic is simple—start with a movement that creates a pump and establishes the mind-muscle connection means that by the time you get to heavier pressing, your pecs are full of blood, warm, and the target muscle is more likely to give out first, not a tendon or ligament.

Third: Incline barbell or dumbbell press. Now that the chest is pumped and the shoulders are prepared, you earn the right to do heavier pressing. John’s incline technique had a specific range of motion adjustment that saved rotator cuffs: do not touch your chest. Stop 2-3 inches short, and drive up. Do not lock out either. Keep constant tension on the pecs. This is what saved John from frequent pec strains and rotator cuff irritation, and it allowed him to actually feel his chest working instead of his shoulders.

He preferred moderate inclines, slight angles rather than extreme ones, consistent with the Dorian Yates approach. John also noted that incline bench presses were among his favorite exercises for building that wide barn door shoulder look from the front. 3-5 sets of 6-8 reps, pyramiding up.

Fourth: Flat barbell bench press, done THIRD or FOURTH, not first. This was the paradigm shift that changed everything. John was explicit: bench press third or fourth in your routine. You will not set any PRs. But make your reduced weight your new frame of reference. If you could bench 315 for 6 when you benched first but can only do 275 for 6 when you bench third, make 275 for 6 your new target — with the confidence that you are so warmed up you will not blow a pec in the process.

Fifth: Isolation, pump work, and loaded stretching. Machine flyes with a full stretch and complete contraction. High-rep Smith machine work with constant tension — all the way down, drive to 3/4 lockout, back down immediately, 15-25 reps. John was convinced that higher rep Smith machine pressing built size and thickness, even while dieting. He saw it work on himself and every training partner he put through it.

One critical positioning note: Stop shoulder packing. For years, the standard advice was to get your shoulders as far down and back as possible before pressing, pack them into the bench. John followed this advice for a long time and taught it to others. But he came to believe it was wrong, crediting Kassem Hanson of N1 Education for changing his mind. When you pack your shoulders down aggressively, your scapula cannot rotate properly, your humerus cannot move forward fully, and you actually lose pec contraction at the top of the movement. Long term, it contributes to shoulder problems.

The correction: do not worry about packing your shoulders down as far as they will go. Just stay tight with a slight static arch, neutral spine and keep your ribcage expanded through breathing. When you press to the top, allow your shoulders to come forward enough to get a full pec contraction, but do not cave your chest in. The balance point is between packed-down immobility and inverted spoon collapse. Let everything move naturally.

Part 6: The Top Chest Exercises

Training the chest is not about using any ONE tool. It is about knowing your angles. So long as you work all three angles for chest, you can select your exercises however you want.

Is flat DB pressing better than flat bench pressing versus a flat Hammer Strength press? They are all equal. Which one feels better to YOU and recruits the chest more? You will find common preferences, but every one of you reading this IS unique. The exercises you like will not be the same as the next guy.

Two factors determine exercise selection. First: does this work the muscle you are trying to work? Do you actually feel this in your chest? Second: can this exercise be progressed with progressive resistance and progressive overload?

The following are favored chest movements that John and I both liked.

1. Flat Dumbbell Press. As long as dumbbells and benches have existed, this exercise has existed. It WORKS. DB pressing works for everyone. Most veteran bodybuilders consider DB pressing superior to bench press, and for good reason, vastly better pec engagement, you can adjust the movement to your body, and it is far safer to perform. You do not need a spotter if you have to bail.

2. Flat Machine Chest Press. A well designed chest press is a fantastic chest builder. A poorly designed one is awkward and useless. Hammer Strength equipment is generally well designed, but the only way to determine if a machine is effective is to get on it and see how it feels.

3. Low Incline Pressing (15-30 Degrees). This is not a specific exercise but an angle range. The 15-30 degree range is where you will work the most pec muscle with an emphasis on the upper pecs. This angle range is always less stressful on the rotator cuff and shoulder joint. You can use ANY implement, DBs, barbell, Smith machine, cables. DBs are the most practical. Smith machine pressing also works very well and is safer than the barbell, and can be progressed very heavy. If you want to emphasize middle and upper chest, stick with low incline pressing in this range and let the gains come.

4. Incline Barbell Press. John’s technique on these was specific and non-negotiable. Do not touch your chest, stop 2-3 inches short. Do not lock out, drive to about 80% lockout and come right back down. This range of motion keeps constant tension on the pecs and saved his rotator cuffs from chronic strain. Use a slight incline, not a steep one.

5. Cable Press. If you are a tall guy with long arms and dont have great chest genetics, you must try these. They can be done low, middle or high. Dont press the handles like you are bench pressing. Bring them together, use elbow bend, get a pec stretch, and treat it like the isolation movement it is.

6. Pushups. Everyone can do pushups. There is no man on earth that pushups do not work for. They work the pecs, shoulders, and triceps altogether. 50 pushups in a row is an achievable strength standard for any man. Start with the standard moderate grip, hands outside shoulder width. Do not overcomplicate this.

Part 7: Volume Periodization, How Much Does Your Chest Actually Need?

The mistake most guys make is piling up direct chest volume on top of already high indirect volume on the shoulders. They flat bench heavy, then incline bench heavy, then do 4 exercises of flyes,

they dont account for the shoulder joint being involved in all of this, and thats without any direct shoulder training,

then they wonder why their shoulders ache and their chest looks the same as it did 6 months ago.

With Meadows-style intensity techniques, forceful contractions, controlled eccentrics, loaded stretches, peak contraction holds, you do not need a high number of sets. The techniques do the work. Intensity takes precedence before volume.

But volume still matters. It just has to cycle.

Weeks 1-3: Medium Volume. 10-12 total direct sets for chest per week. 3-4 exercises. Focus on execution, mind-muscle connection, and establishing the intensity techniques. Do not add more, master what you have.

Weeks 4-9: High Volume. 12-16 total sets per week. Four to five exercises. Your body has adjusted to the intensity from the first phase, so you keep it off balance by adding more overall volume and total tonnage. This is where you bring in Smith machine constant tension work, rest-pause flat bench, pec minor dips, and drop sets. Add frequency — hit chest twice per week if recovery allows. Six weeks of grinding.

Weeks 10-12: Low Volume, Maximum Intensity. Drop to 8-10 total sets. Almost exclusively high intensity sets. Every set goes to failure or beyond. Drop sets, rest-pause, partials. This is the peak. You are squeezing the last drop of growth out of the stimulus you built over the previous nine weeks.

Weeks 13-14: Deload. 1-2 weeks of light training. Not optional. How do you know when you need it? John listed the signs: elevated resting heart rate, inability to generate force on heavier compound exercises, difficulty sleeping, sudden bad moods. The shoulder joint accumulates fatigue differently than muscles do. Tendons and ligaments need recovery time. The growth you see during the deload is often the most satisfying of the entire cycle.

Balancing Chest with Shoulder Training

If you train chest and shoulders on separate days, be mindful of total pressing volume. Heavy bench pressing on Monday and heavy overhead pressing on Wednesday means your front delts never recover and your shoulders accumulate damage. Either combine them on the same day (chest first, shoulders after) or ensure at least 72 hours between heavy pressing sessions.

John’s preferred approach was training shoulders after chest on push days. The front delts are already warm and pumped from pressing, so you can focus shoulder work on lateral and rear delts where it matters most. This prevents total weekly pressing volume from getting out of control.

Part 8: Strategic Failure

This is one of the most important concepts in John’s training philosophy—most people do not push hard enough.

He would rather see someone go to failure than always have reps in reserve. But he did not believe you should go to failure on every set.

If you are doing four exercises for chest at three to four sets each, that is 12-16 total sets. John said he personally could not go to true failure 16 times in a chest workout. Nobody can and be honest about it. What he wanted was one or two sets per exercise taken to complete failure, with the other sets being hard but not maximal.

Here is where the intelligence comes in. Where you go to failure depends on the equipment.

Barbells: Do not go past failure. Once form breaks on a barbell bench—flat, incline, or decline, rack it. Do not keep grinding with ugly reps until someone has to pick the bar off of you. That is how people tear pecs. Get your clean reps, rack it, move on.

Dumbbells: You can go to failure and even do a few partials after. You are in a safer position, if you fail, you drop the dumbbells. Drop sets work here too.

Machines: Now you can go beyond failure. Forced reps with a partner. Drop sets. Iso holds. Partials out of the stretched position. You are in a position of complete safety, so this is where you push the intensity past what you would ever attempt with a barbell. When the burning starts, your set starts.

John structured his programs around this principle: barbell work stays clean and controlled, and then as the workout moves to dumbbells and machines, the intensity techniques escalate. The barbell builds the foundation. The machines finish the job.

Advanced Techniques

Rest/Pause. These work best with machine presses and flat barbell bench done later in the routine. Set to near failure, rack the weight, rest 10-15 seconds, explode for more reps. John loved rest/pause on flat bench specifically because there is no fear of injury resting and exploding off your chest after you have already done 2-3 exercises and the pecs are gorged with blood.

Constant Tension. On almost all barbell chest exercises, lower with a controlled tempo and drive to 3/4 lockout before lowering right back down immediately. No resting at the top. No resting at the bottom. Combined with higher rep ranges of 15-25, this builds size and thickness that standard heavy low-rep pressing cannot replicate.

Partials. Performed out of both the stretched and contracted positions on machine exercises. On a Hammer Strength press: do 10 full reps, then pump out partial flexes at the top for 6 more. Or do 10 full reps followed by 20-30 partial reps out of the bottom for blood flow. Save these for machines where the movement path is controlled.

Drop Sets. Machines only, Smith, Hammer Strength, Cybex. John was not big on doing them with dumbbells because the arms give out too quickly. You are after deep pectoral stimulation, not triceps stimulation.

3-Second Descents. Free weight pressing with deliberate slow negatives forces the pecs to control the load through the entire range. Best on barbell inclines and flat presses, not on machines where the triceps take on too much work during slow eccentrics.

The Quint Press-and-Stretch. John learned this from John Quint, a myofascial therapist with one of the thickest chests he had ever seen. In between pressing sets, take a flexible band and perform a stretch that opens the pecs under tension. The pump reaches an insane level when you perform these with pecs already full of blood.

Part 9: Smart Chest Training Strategies

Strategy 1: Train your chest from all three angles with one exercise per angle. This ensures even development top to bottom.

Strategy 2: If you seriously lack upper chest and shoulder development, perform one exercise on a flat angle, one on a low incline, and one on a high incline.

Strategy 3: If you have a history of shoulder pain, impingement, pec tears, or bad posture, then put barbell pressing 3rd or 4th, or take it out entirely if it causes issues. Heavy bench pressing is not something most lifters can keep up past their 50s.

Strategy 4: Don’t start a workout with dips. They tend to fatigue the pecs heavily because the muscle is fully stretched and fully contracted. This compromises performance of other movements. They are best done last. This also ensures your shoulders and pecs are fully warmed up before doing them.

Strategy 5: Take the longest warmup for the first exercise. Once your chest and shoulder joint are pumped and working, you don’t need long warmups for your 2nd and 3rd exercises. For the first one, warmup in 2-3 sets of light to moderate weight before working sets.

Strategy 6: Go heavy and low reps (5-8) on only ONE of the exercises each workout. This stimulates the full range of fiber sizes. training strength, hypertrophy, and strength endurance all at once. Assuming three exercises: heavy exercise with working sets of 6, medium exercise with working sets of 8-10, light exercise with working sets of 10-20. Medium and light do not mean easy. They mean you are using weights at a less intense rep range relative to your 1 rep max.

Strategy 7: Stretch your pecs after training. Bad posture is already an epidemic, and getting tight pecs reinforces it. You do not want tight pecs pulling your shoulders into internal rotation and limiting range of motion. After training chest, stretch your pectorals for 2-3 minutes.

Strategy 8: If you seriously struggle with mind-muscle connection and the pecs are a weak muscle group, do the following: start with cable flys at low, middle, and high angles for 2-3 sets, squeezing the pecs and internally focusing on every set. Then perform ONE compound movement that you can feel the pecs working on. Pyramid up , 20 reps, then 15, then 10, then a hard set of about 8 reps to positive failure. Do this workout no more than twice a week for 6 weeks. I guarantee you will experience more pectoral growth than in the prior 6 months.

Use a mix of equipment. A lot of people are all “machines suck, they’re terrible, you should use barbells.” Then some people are all machines and never touch heavy barbell work. The answer is somewhere in the middle. John could not imagine not doing barbell work — a low incline barbell bench was his favorite exercise for chest. But he also could not imagine not using machines, which allow you to go to failure safely, work through controlled ranges of motion, and apply intensity techniques that would be dangerous with free weights. Dumbbells give you the natural arc and full stretch that barbells cannot. Cables give you constant tension that nothing else replicates. Use all of them. The sequencing matters more than the equipment.

Part 10: Troubleshooting Common Chest Problems

Stubborn Upper Chest. The most common complaint. Start every chest workout with incline work, no exceptions. Use 30-45 degree angles, not steeper. Emphasize dumbbell pressing over barbell for the greater range of motion. Implement daily activation work — 2-3 sets of light incline flyes every morning takes less than 5 minutes and will transform your upper chest development within 8-12 weeks. John found that most upper chest problems were not training problems. They were sequencing problems. Put incline first. Always.

Shoulder Pain During Chest Training. The number one chest day complaint. The fix starts with what you do before you press. Rear delt activation, rotator cuff work, and proper positioning should precede every chest session. Switch from barbell to dumbbell pressing. Reduce range of motion temporarily if needed. Focus on horizontal adduction movements rather than pure pressing. Face pulls every single workout, regardless of which body part you are training.

Lack of Inner Chest Development. Implement squeeze press variations. Use cable crossovers at multiple angles with a hard squeeze at the midline. Add isometric holds at peak contraction on every flye and crossover movement. The inner chest responds to constant tension and peak contraction, not heavy loads.

Flat, Shapeless Chest. This is usually a fiber recruitment problem, not a size problem. Stop doing exclusively flat pressing. Train all three regions with targeted angles. Add constant tension work with cables. Implement peak contraction holds on every isolation exercise. Use loaded stretching. It takes 12-16 weeks to see the shape change.

Chest Imbalances (Left vs. Right). Address the weaker side with a 2:1 volume ratio. Use unilateral training, single-arm cable flyes, single-arm dumbbell presses. Start every set with the weaker side. Match reps on the stronger side. Do not allow the strong side to compensate.

For Tall Lifters (6ft+): Long arms mean longer levers on pressing movements. You will not press as heavy as shorter lifters. Accept this. The mechanical disadvantage is real and permanent. Focus on dumbbells over barbells. Higher reps on pressing movements, always. 8-15 rep range. Cable and machine work are your best friends because they provide constant tension throughout the full range of motion that your long arms travel through. Do not get caught up in bench press numbers. Train the muscle, not the movement.

Part 11: Chest Workouts

Two complete chest sessions using the Meadows four-phase system — one for Phase 1 (medium volume) and one for Phase 2 (high volume).

Workout A: Phase 1 (Weeks 1-3)

A1. Band Pull-Aparts — 3 x 20 Controlled tempo, squeeze the shoulder blades at the back. Activate the rear delts and prepare the shoulders. (Activation)

A2. Light Cable Flyes — 2 x 15 Establish the mind-muscle connection. Feel the chest working, not the front delts. Slow and deliberate. (Activation)

B. Flat Dumbbell Twist Press — 3 x 10 Lie flat or on a slight incline. Lower the dumbbells with an arched chest for a deep stretch. As you drive up, turn your pinkies IN toward each other and squeeze hard at the top. (Phase 1)

C. Incline Barbell Press — 2 warm-up sets, then 3-4 x 8 Slight incline. Stop 2-3 inches above the chest. Drive to 3/4 lockout. Constant tension. Pyramid up in weight until you cannot get 8 reps. (Phase 2)

D. Machine Press and Stretch — 3 x 10 + 10 Do 10 reps on a chest press machine. Get up and perform 10 band press-and-stretches. 3 rounds. (Phase 3)

Workout B: Phase 2 (Weeks 4-9)

A1. Band Pull-Aparts — 3 x 20 (Activation)

A2. Light Cable Flyes — 2 x 15 (Activation)

B. Incline Dumbbell Press — 4 x 8 Pyramid up. Full stretch at the bottom. Drive to lockout and squeeze. Last set to failure. (Phase 1)

C. Smith Machine Slight Decline Press (Constant Tension) — 4 sets: 25, 20, 12, 8-10 reps. Wide grip. Lower to chest, drive to 3/4 lockout, right back down. Last set: go to failure, drop the weight and rep out, widen grip and rep out again. (Phase 2)

D. Flat Barbell Bench Press (Rest/Pause) — 4 x 6 R/P Lower with control. Pause on chest for 2 seconds. Explode up. Rest 10-15 seconds between clusters. Perfect form, explosive intent. (Phase 3)

E. Pec Minor Dips — 3 x Failure Arms straight throughout. Lower to a full stretch. Raise by flexing the chest. Add weight if possible. (Phase 4)

Finish: Band press-and-stretch — 10-15 reps between the last two exercises, or as a standalone finisher. (Phase 4)

R.I.P. John Meadows, I've learned the vast majority of what I know about lifting weights from his articles, videos, and the kind times he answered my gigantic DMs. He's a legend.