Mountain Dog Back Training

The back is the most complex muscle group to develop and the most neglected. Not because it’s hard to train, the exercises aren’t complicated, but because you can’t see it in the mirror.

As a result, many people fail to develop both a mind muscle connection and effective exercise technique when it comes to back training.

John himself found that back was his most stubborn overall muscle group. Arms and legs he had genetic talent for, chest grew well well, shoulders took some work, but back was the one area he lacked in his bodybuilding career. Its also arguably where he made the biggest impact in bodybuilding training. Meadow rows being the most prominent example.

John’s back training philosophy was born from years of experimentation, anatomical study, and practical application in both his own training and with hundreds of clients. He recognized that the back was the most complex muscle group in the body, requiring multiple angles, grips, and movement patterns to achieve complete development. Per his own words

“The back is like a symphony orchestra”

“You have all these different muscles that need to work together, but each one also needs to be developed individually. You can’t just do pulldowns and rows and expect a complete back any more than you can play a symphony with just violins.”

This article covers everything: the anatomy, the exercises, the sequencing, the rep ranges, the technique cues, and the workout templates. Between John’s methodology and my own training and coaching experience, I’m giving you the complete system.

What you’ll learn:

Why your back has four distinct superficial muscles that each require different movement patterns, and why most guys only train one of them well

The difference between vertical pulling and horizontal rowing, and how to use both to build width and thickness

The Meadows Rows that John made famous

The ideal exercise sequencing for growth

periodization for back training

Before We Begin

Ive been using NMN the past 3 months. NMN (Nicotinamide Mononucleotide) is a direct precursor to NAD⁺ that supports cellular energy production, mitochondrial function, and age-related metabolic resilience by helping restore declining intracellular NAD⁺ levels. Use code AJAC10 at checkout

High Tech Health Saunas is having sale. Mention AJAC at purchase and youll get an even better one.

For the men that want their health dialed in with the best doctors in the world, work with Velocity

Part 1: Functional Anatomy

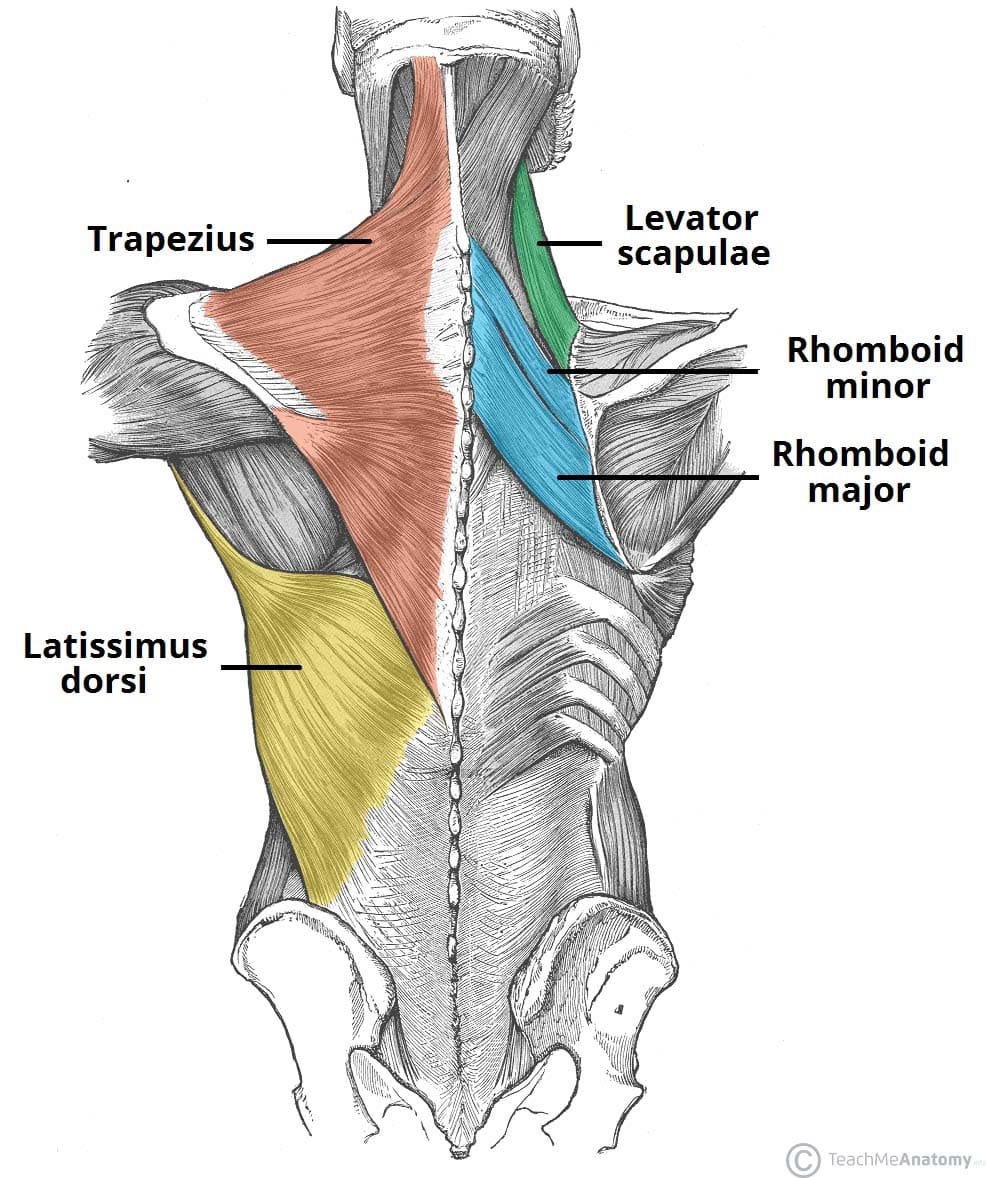

The muscles of the back fall into three layers—superficial, intermediate, and deep. For our purposes, we’re training the superficial muscles. These are the large muscles visible on a developed physique. When you train them with sufficient intensity, the intermediate and deep layers receive stimulus automatically. You do not need to worry about them separately.

Latissimus Dorsi —The Wings:

The largest muscle of the upper body, covering from the upper pelvis and lumbar spine all the way to its insertion on the arm. John divided the lats into functional regions that respond to different training stimuli:

Upper Lats: Responsible for the wide V-taper, best developed through wide-grip pulling movements. Peak lat torque occurs between 30–50 degrees of shoulder flexion during horizontal pulling, which explains why rows often build more lat mass than pulldowns.

Lower Lats: Creates the dramatic sweep into the waist. Responds to narrow-grip and neutral-grip work, particularly supinated pulldowns and close-grip cable rows. The lower lat region activates most strongly as the arm moves from overhead toward the hip, plateauing around 40–50 degrees of shoulder flexion.

Trapezius—The Three-Headed Beast:

The traps are three distinct functional units, not one muscle:

Upper Traps: Originate near the base of the skull, responsible for shoulder blade elevation. Peak recruitment during heavy carries, shrugs, and deadlift lockouts. Evidence supports that loads around 80% of 1RM produce the greatest upper trap activity, and holding contractions at the top of shrugs was one of John’s signature techniques.

Middle Traps: Best targeted through horizontal rowing with scapular retraction. Research shows that a supinated grip during bent-over rows produces greater middle trap recruitment due to the increased range of motion into shoulder extension.

Lower Traps: The most neglected region, critical for scapular upward rotation and shoulder health. Activated most during the first half of vertical pulling movements (pulldowns and pull-ups) where scapular depression occurs. Prone Y-raises with external rotation are among the best isolation exercises for this area.

Rhomboids:

While not visible, the rhomboids contribute to overall back thickness. They sit beneath the middle and lower traps, primarily fast-twitch in fiber composition. Their function is to adhere the shoulder blade to the rib cage during horizontal pulling and to produce downward rotation and retraction.

Chest-supported rows are particularly effective for rhomboid recruitment because removing the need to stabilize the erectors allows greater torque and muscle recruitment along the midback.

Erector Spinae:

A cluster of nine muscles running from the sacrum to the skull, divided into the spinalis, longissimus, and iliocostalis groups. John trained these primarily at the end of back sessions to avoid fatiguing them before heavier compound work.

Teres Major:

The “Mini Lat”: Often overlooked but crucial for complete upper back thickness.

Rear Delts:

The Balance Creators: Essential for shoulder health and complete upper back development.

“When people say they want a bigger back, they usually mean they want wider lats,” John observed. “But width without thickness looks flat, and thickness without width looks narrow. You need systematic development of every area, and that requires understanding what each muscle does and how to target it specifically.”

Part 3: Technique Fundamentals

Pulling mechanics and bicep tendon health. The most common cause of biceps tendinitis in back training is incorrect forearm alignment. On every pulling movement, the forearm and elbow must track directly in line with the resistance. If you are inadvertently curling the weight — if the forearm is doing the work rather than the elbow traveling toward the body — you are chronically loading the biceps tendon at a disadvantaged angle. This causes pain eventually in most people. A false grip (thumb draped over the handle rather than wrapped under) can reduce tendon irritation. Lifting straps are appropriate and beneficial — contrary to gym mythology, using straps does not weaken the grip over time.

Neck and upper trap compensation. If back training causes neck tightness or pain, the most common cause is over-recruitment of the upper traps. Many lifters unconsciously elevate their shoulders and pull with the upper traps rather than retracting the shoulder blades and driving the elbows back. The fix is deliberate: on every pull, actively think about driving the elbows toward the floor, not pulling the bar toward your face. Your neck should not be working during a pulldown.

Spinal positioning. Lat-focused work requires a neutral spine. Upper back and trap-focused work benefits from a slight thoracic arch — a natural extension through the mid-back — which opens the shoulder blades and allows full retraction. Never round the lower back to get a longer range of motion, and never hyperextend to move more weight. Both patterns shift load off the target muscles and onto passive spinal structures.

The Two Directions of Back Training

Everything in back training reduces to two movement patterns.

Vertical pulling. This means the arm travels overhead and then pulls down toward the body — chin-ups, pull-ups, pulldowns. Vertical pulling primarily loads the costal and lumbar/iliac fibers of the lat, building width and the lower lat sweep.

Horizontal rowing. This means the arm travels in front of the body and pulls toward the torso—every variation of rows. Horizontal rowing primarily loads the thoracic lat fibers and the trapezius, building thickness and mid-back density.

A complete back program requires both. You need to train the lats for width with pullups and pulldowns, and then train the middle fibers of the back for density.

The grip you use within each pattern matters. Supinated grip (underhand) during vertical pulling increases the stretch on the lat and places slightly more tension on the lower fibers. Neutral grip allows slightly more weight and greater bicep recruitment. Wide pronated grip shifts emphasis toward the upper lat and upper back. Vary all three across your training cycle.

Part 4-The Sequencing of Mountain Dog Back Training

John allowed for creativity with back training, but he did follow a specific format.

Activation and Postural Preparation

As he got older, John began every back session with activation work designed to wake up dormant muscles and establish proper movement patterns. None of these mandatory, they are performed on a as-needed basis.

Activation Protocol:

Band pull-aparts for rear delt activation

Prone Y-raises for lower trap activation

Cat-cow stretches for thoracic mobility

Light lat pulldowns focusing on muscle feel (supinated grip for lower lat emphasis)

The Meadows Back Activation Sequence:

20 band pull-aparts (posterior activation)

15 prone Y-raises (lower trap activation)

10 cat-cow stretches (mobility prep)

Light supinated pulldowns focusing purely on lat feel—drive elbows back, not down

Lat Activation Drill: Before any pulldown or rowing movement, John used a specific lat activation technique: light cable straight-arm pushdowns performed slowly, focusing entirely on initiating the movement from the lat rather than the arm. This drill was recommended before every back session and was particularly effective for trainees who struggled to establish mind-muscle connection with their lats.

“Most people’s backs are shut off from sitting at desks all day,” John explained. “You can’t just jump into heavy rowing and expect dormant muscles to suddenly start working. You need to wake them up first.”

Exercise 1: Row First, Unilateral

John was very fond on unilateral rows at the very beginning of the workout. Rows take tremendous energy and they are undeniable mass builders, John wanted them done at peak capacity.

The Meadows Row—John’s most famous creation, and the exercise more responsible for the mass and detail on his lats than any other. He admitted he probably didn’t invent it, but he’d never seen anyone else doing them, so he staked his claim.

Setup: Stand next to the business end of a T-bar or landmine, where you’d normally add a plate. Grab the bar end with one hand and row. Always use straps. The critical technique point is hip position — “kick” your hips away from the bar to increase the stretch on the entire lat, especially the lower lat. When you find the right position, you’ll know. Use 25-pound plates for even greater range of motion. Drive the elbow, not the hand. 2 warmup sets, then 3-4 sets of 8-10.

One-Arm Barbell Row — Stand beside a loaded barbell, grasp the bar, and row. Like the Meadows Row, emphasize the stretch on the way down. Use 25-pound plates for maximum range of motion.

Mountain Dog Dumbbell Row — Standard one-arm row but ditch the bench. Support yourself on a dumbbell rack with a split stance. This pre-stretches the lat and leads to a greater contraction.

Chest-Supported Incline Rows — Removes lower back pressure by supporting a simulated bent-over position. Allows maximum force production per rep. These can be done with DBs or a Tbar setup.

Exercise 2: Stretch Movement

Once blood is in those lats, they’re ready to be stretched. This is where you do your pulldown/pullup movements. Examples of exercises

This sequencing matters for two reasons. First, stretch movements can be dangerous on unpumped muscles, cold muscle plus heavy weight plus ego equals disaster. Second, with intra-workout nutrition flowing, your primed back will take up nutrients into the muscle cells.

Exercise 3 and: Traps and Rhomboids

Traps and rhomboids can technically be trained at any point, but they sit naturally in the third slot. This is where the wide grip rows would be done. The universal technique point: keep elbows higher than you think they should be. If elbows drop, the lats take over and the traps/rhomboids lose stimulation.

Supported Rows with 1-Second Flex — Any machine that supports the chest. Elbows up, pull back, flex. Multiple angles work — sitting upright, tilted on a pad. The support lets you focus purely on elbow alignment and squeezing.

Seated Wide Grip rows — When doing seated rows, bend forward at the waist on every rep, and then pull with the elbows back to an upright neutral spine position.

After rows, the you’d move onto your shrugs and possibly rack pulls

Dumbbell Shrugs with 3-Second Pause/Flex — 12-15 reps with a deliberate 3-second hold and flex at the top of every rep. Shrug up and back, not just up. No bouncing.

Rack pulls — John liked these done for sets of 5-6 reps. You could go heavy and ramp up the weight. The bar should be set to around knee height or slightly lower.

Band Shrugs — Bands create tremendous tension at the top where the traps are strongest. Attach to power rack pegs. 3 sets of 12 with 2-second pause at top.

Exercise 5: Spinal Erectors Last

Always save spinal erector work for last. The one exception: if you can deadlift without your lower back burning or tightening, you can move that movement earlier. But doing hyperextensions before Meadows Rows? Bad idea.

Deadlifts (Blocks or off the Floor) — Deadlifts didn’t give John huge wide lats, but they helped with lower back development. Cranking out deadlifts after all the other back work is brutal, but it works.

Hyperextensions—They work for everyoneHis preferred protocol: hold a 50lb dumbbell for 15 reps, drop it, gut out 10 more. Next set, 25lb dumbbell same protocol. Third set, bodyweight for 25 reps. Brutal.

Part 5: The Top Exercises

These are mix one John and mines personal favorites. As always, experiment to find yours.

The Meadows Row. John’s signature exercise and the most famous movement he created. Set up a barbell in a landmine attachment or wedge one end against a wall. Straddle the barbell, grip the end with one hand using an overhand grip, and row the weight toward your hip—not your chest. The key is the hip-oriented row path and the free-arm support. This position allows a tremendous range of motion and eliminates lower back stress while delivering full lat and upper back stimulation. More than anything, this is the exercise that convinced serious lifters to take unilateral back work seriously.

The Chin-Up. The single best compound lat exercise available. It stretches the lat fully at the top, contracts it completely at the bottom, and recruits the muscle in a way that pulldowns approximate but rarely replicate. If you cannot yet do chin-up reps, use the pulldown as a direct substitute and work toward the chin-up as a strength target. The semi-supinated or neutral grip version works well as an alternative or progression.

Wide-Grip Pulldown. While not John’s primary choice, the wide-grip pulldown is the best tool for building upper lat width. The wider grip shifts emphasis from the costal fibers toward the thoracic upper-lat region. John included these as a secondary exercise when upper back width was a priority. Pull the elbows tight to the body, whether the bar touches the sternum depends on your arm length and anatomy.

Seated Cable Row. The standard of horizontal back training. John used the neutral grip attachment most often for maximal lat recruitment. The seated cable row allows precise control of the elbow path and upper back positioning, and it scales well with progressive overload over long periods. One technical note: Bend forward at the waist on every rep, butdo not allow your torso to swing back past neutral as the weights increase. If your body is compensating with momentum, the weight is too heavy.

Chest-Supported T-Bar Row / Chest-Supported Dumbbell Row. John’s preferred trap and upper back compound movement. The chest-supported position eliminates lower back involvement entirely, forcing the rhomboids, traps, and upper lats to do all the work. Row with the elbows at roughly 45 degrees from the body — this is the optimal angle for middle trap recruitment. John called this kind of work essential for anyone who wanted dense, thick upper back development.

Dumbbell Shrug. The simplest upper trap exercise, and one of the best. John included shrugs in most back sessions because the upper trap and levator scapulae respond well to direct work. Do not roll the shoulders — the traps do not generate rotational force. Simply elevate and hold briefly at the top.

1-Arm Cable Row / 1-Arm Cable Pulldown. A great unilateral tool. Cables maintain tension through the full range in a way that dumbbells don’t. For anyone who has difficulty feeling the lat work during bilateral rows, switching to unilateral cable work is often the immediate solution.

Part 6-Addressing Common Back Training Problems

John’s systematic approach was particularly effective for solving typical back development issues:

For Lack of Width (V-Taper):

Prioritize wide-grip chin-ups and pulldowns (pronated wide grip shown to produce superior lat activity)

Emphasize lat stretch and contraction on every rep

Minimize bicep involvement by focusing on elbow drive rather than hand pull

Use away-facing pulldowns to isolate contraction quality

For Lack of Thickness:

Emphasize rowing movements at multiple angles

Use various grip positions systematically—supinated for middle traps, pronated wide for posterior delts and rhomboids

Focus on squeezing shoulder blades together on every row

Implement dead-stop training to eliminate momentum

Add chest-supported row variations for pure midback isolation

For Weak Lower Lats:

Begin every session with supinated pulldowns focusing on driving elbows back (not down)

Use single-arm cable pulldowns with a slight lateral trunk bend toward the working side

Implement Meadows Rows with deliberate foot positioning to target the lat sweep

Cable rows pulled to the lower abdomen with supinated or neutral grip

For Underdeveloped Spinal Erectors:

Add Louie’s Special or banded hyperextensions at the end of every back session

Control the eccentric phase of deadlifts rather than dropping the bar

Implement reverse hyperextensions 2–3 times per week

Use deficit deadlifts periodically to increase range of motion and erector demand

For Postural Problems:

Increase rear delt training frequency to daily

Emphasize lower trap development through prone Y-raises

Stretch anterior chain regularly

Strengthen deep neck flexors

For Imbalanced Development:

Use unilateral training (Meadows Row, one-arm barbell row, single-arm pulldowns) to address asymmetries

Address the weaker side first in workouts

Monitor and correct form constantly—video yourself from behind during rowing movements

Part 7-Intensity Techniques: What Works and What Doesn’t for Back

John was particular about intensity techniques with back

Rest/Pause — Works especially well with rows and allows you to get in quality reps

Continuous Tension — Focus on squeezing the target area on almost all back exercises, no pausing at the top of bottom of the rep. The mind-muscle connection is harder to establish with back muscles than any other group. Continuous tension overcomes this.

Partials—Apply to any pulldown or chin variation at the stretched part of the movement. On cable or machine rows, you can do some loose not quite cheating reps at the end.

John was not fond of the following:

Drop Sets—On back training your arms or grip can fatigue before back and your technique can get wonky, even with straps. Use this technique sparingly if at all.

Three-Second Descents—Doing low cable rows or pulldowns with slow negatives causes the arms and shoulders to take over for the lats. Great for legs, not for back.

Part 8: Volume — How Much Back Training Do You Actually Need?

The 12-Week Periodization Model

Weeks 1-3 — Medium Volume (11-14 sets): New exercise angles create new stimulus. Let the novelty do some of the work. You won’t need a ton of sets because the intensity carries.

Weeks 4-9 — High Volume (16-20 sets): Your body adjusts to Phase 1 intensity, so keep it off balance by adding volume each week. More high-intensity sets layered in progressively. Six weeks of grinding. This is where back development really happens — the accumulated work over these six weeks drives the majority of new growth.

Weeks 10-12 — Low/Medium Volume (8-10 sets), Maximum Intensity: Volume drops, but every set is the hardest you’ve done in your life. Almost all sets are high-intensity, preceded by proper warmup. Quality over quantity at the extreme end. Your nervous system has been accumulating fatigue for nine weeks — now you capitalize on it with concentrated, maximal effort.

Deload — 2 Weeks: Light training. Signs you need it: elevated resting heart rate, difficulty sleeping, poor mood, difficulty generating force on compound exercises. Everyone is different, but two weeks is John’s general recommendation after a brutal 12-week cycle. The rebound from this deload — the supercompensation effect — is where a significant portion of actual growth becomes visible.

Training Frequency: How Often to Train Back

John generally recommended training back once per week with full intensity using his system. The volume and intensity of a proper Mountain Dog back session creates enough stimulus and enough damage that a full seven days of recovery is warranted for most trainees.

However, for back specialization phases, John would sometimes program two back sessions per week — one heavy session following the full five-principle sequence, and one lighter session focused on stretch movements and pump work with reduced load. The lighter session served as an active recovery day that drove additional nutrient delivery to recovering tissue without adding meaningful fatigue.

For trainees running a push/pull/legs rotation, back was the centerpiece of every pull day. John would program heavy row emphasis on one pull day and stretch/pump emphasis on the next, naturally rotating through the exercise catalog over multiple weeks.

A Sample Workout

Phase 1 Sample Workout (12 Total Work Sets)

A medium-volume session from the first three weeks — establishing new movement patterns and building the intensity base:

A. Meadows Rows — 2 warmup + 3 x 10. Focus on perfecting hip position. Moderate weight, feeling every fiber.

B. Stretchers — 2 x 12. Establish the shoulder girdle mobility for the weeks ahead.

Fascia Stretch: 1 minute each lat, twice

C. Band Shrugs — 3 x 12. Two-second hold at top. Build the contraction habit.

D. Reverse Hyperextensions — 3 x 15. Moderate load, controlled tempo. Build the spinal erector base.

Final Points

John’s back development was a product of attention — to anatomy, to technique, to which exercises actually work and which are just impressive-looking. He built a system that produced results across multiple decades because it was built on principles, not on chasing whatever exercise happened to be popular.

The back rewards that same attention. You cannot fake a developed posterior chain. You either trained it seriously or you didn’t, and the difference shows.

Train both planes. Vary your grips. Master the full range of motion before adding weight. Use unilateral work to correct imbalances. And be patient — back development takes time, but done correctly, it is the development that makes everything else look better.